This article by Kristin M. Murphy, Amy L. Cook, and Lindsay M. Fallon of the University of Massachusetts Boston originally appeared on kappanonline.org. It’s being republished here with the authors’ permission. The group recently presented during our Future of Education Roundtable Series; sign up for future sessions here.

Those of us who work in K-12 education have only begun to make sense of the many consequences the COVID-19 pandemic has had for our students. Months of remote teaching and learning have made one thing quite clear, though: The academic, physical, and mental health benefits of in-person schooling are difficult to replicate through online instruction.

And yet, while technology hasn’t been — and may never be — a perfect substitute for face-to-face interaction among students and teachers, it can provide powerful scaffolded learning opportunities to support children’s development. Over the past five years, and in collaboration with education researchers and practitioners, we have explored the potential of an educational technology called mixed reality simulations (MRS) to help children learn and practice a number of important interpersonal skills.

Consider how common it has become, in recent years, for pilots to use flight simulators to help them practice difficult maneuvers, or for surgeons to rehearse medical procedures in simulated operating rooms. Similarly, we’ve found that students can learn and strengthen specific interpersonal skills by interacting with avatars (i.e., digital representations of people) in a safe, learning-oriented space, then receiving guidance and feedback from a teacher or mentor (Murphy, Cash, & Kellinger, 2018).

To date, MRS technology has been used mainly with college-level students training to become teachers, counselors, or nurses. However, having seen its value for the graduate and undergraduate students at our university, we wanted to know how this technology might facilitate social-emotional learning (SEL) among young children.

SEL and COVID-19

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL, 2020a) defines SEL as “the process by which children develop the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to interpret and manage emotions, identify and strive toward positive goals, feel and display empathy for others, build and sustain positive relationships, and implement responsible decisions.” Comprehensive SEL programming across a child’s educational experiences has the potential to promote healthy interactions between children and their surroundings and promote academic achievement (Mahoney, Durlak, & Weissberg, 2018).

The COVID-19 pandemic has further elevated the importance of SEL. During the pandemic, children have experienced substantial reductions in social contact with their peers, with many being required to attend school remotely or in a hybrid fashion. A comprehensive review of literature on young people’s mental health during COVID-19 found that children and adolescents are showing increased symptoms of irritability, inattention, fearfulness, clinginess, disturbed sleep, nightmares, agitation, and appetite disturbance (Singh et al., 2020). To address these negative effects, organizations such as CASEL (2020b) have provided guidelines to help educators, parents, and caregivers support children’s social-emotional learning and development. We believe that MRS can be a useful means of providing such support to elementary-level students, whether they are still learning at home, returning to in-person school, or engaging in a hybrid program.

What are mixed reality simulations?

Mixed reality simulations fall within the category of learning methods broadly known as situated learning methods. Situated learning theory views learning as social in nature and occurring among and between individuals and materials in authentic contexts. From the situated learning perspective, knowledge acquisition and transfer depend heavily on how closely a learning opportunity matches the real-world situation (e.g., the similarity between a simulated classroom and a live classroom; Lave & Wenger, 1991; Putnam & Borko, 2000).

One study found that four 10-minute mixed-reality simulation sessions led to changes in teachers’ behavior in the classroom, further illuminating the power of simulations, used in small dosages.

Examples of situated learning methods include case studies, role-plays, and simulations. Research indicates that case studies may promote better learning outcomes than stand-alone lectures (Yadav et al., 2009), but they do not provide an opportunity for active practice. In comparison, role-play activities allow learners to practice in a safe environment with peers with little to no real-world consequences (Storey & Cox, 2015). A long-standing and diverse body of research across disciplines indicates that role-play can change behavior, attitudes, and knowledge in industries such as health care, the military, and aviation (Murphy, Cash, & Kellinger, 2018). However, while role-playing is a valuable learning tool, it has its limitations as well. For instance, in the field of teacher education, a common role-play tool is microteaching, which requires preservice teachers to plan a lesson, deliver it to classroom peers playing the role of students, and then reflect on the experience (Diana, 2013). But, as researchers have noted, teaching university peers does not authentically mirror the experience of teaching in a K-12 classroom and could lead to oversimplified perceptions of teaching (Brownell et al., 2018; Grossman, 2005).

Simulations have been used in education since at least the 1970s (Cruickshank & Broadbent, 1970), and, in recent years, mixed reality simulations have become increasingly popular in teacher preparation programs. As the number of programs implementing mixed reality grows, so, too, does the research base. For instance, one study found that four 10-minute mixed reality simulation sessions led to changes in teachers’ behavior in the classroom, further illuminating the power of simulations, used in small dosages (Straub et al., 2015).

Two of the most commonly used MRS platforms in education are Mursion and TeachLivE (Hudson et al., 2019). On these platforms, learners interact in real time with racially diverse avatars who might represent school professionals, families, or students in simulated school environments, such as classrooms and school offices.

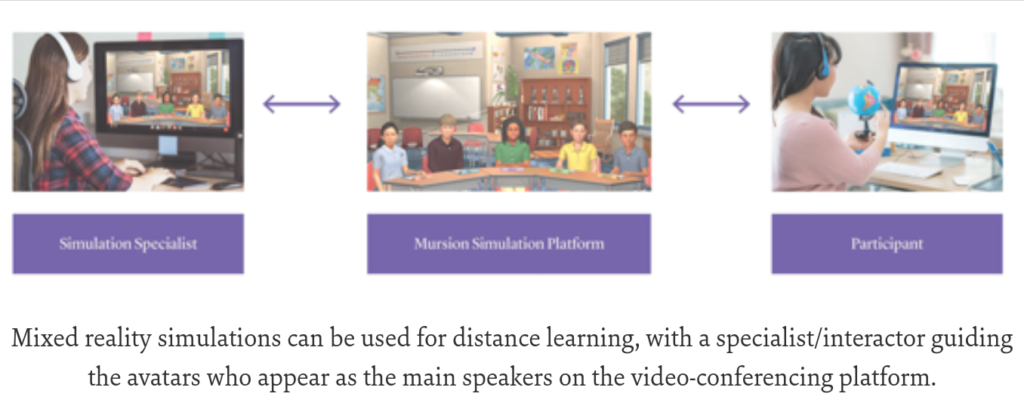

MRS differs from virtual reality because the avatars are operated via a blending of human and artificial intelligence. Working behind the scenes, a human — known as a simulation specialist — controls the avatars’ movements and speech. Some of the avatar behaviors, such as raising a hand, whispering to a peer seated next to them, checking their cell phone, stretching, or adjusting their body in their seat, are automated, but they also can be manually activated (Dieker et al., 2014). One simulation specialist controls all of the avatars involved in a specific scenario, be it a single avatar playing the role of a parent, or a class of five middle school students. And while the student can only see the avatar(s), the simulation specialist can see the student via web camera, allowing them to react, in real time, to the student’s speech, facial expressions, and body language. This makes the simulation much more realistic than is possible using fully automated characters, which can only respond to students in preprogrammed ways.

During a mixed reality simulation, the learner (whether a child, a college student, or an adult) generally stands or sits in front of a large-screen television monitor that displays the avatars and environment, and their classmates sit behind them, serving as observers. Learners might also participate in collaborative team-based simulations (e.g., as teachers coleading a class of avatars) in which group members interact with the avatars while standing or sitting alongside each other in front of the screen (Murphy et al., 2018). Simulations can also occur via video conference on Zoom, with all learners meeting in the specified Zoom room instead of a physical space. The avatar(s) are displayed via speaker view, meaning they take up the largest part of the screen. The learner(s) and coach are displayed in smaller tiles.

During a mixed reality simulation, learners closely focus on one or two discrete skill(s) for 7 to 10 minutes, often as a precursor or complement to real-life experiences (Driver, Zimmer, & Murphy, 2018). During this brief simulation, learners experience a suspension of disbelief, where they temporarily accept the avatars and situation as real (Hayes et al., 2013), but this effect begins to wane with a longer time frame.

Using MRS, students and their coach(es) can focus on discrete tasks in a way that is difficult to replicate in unpredictable real-life situations. For example, a preservice teacher can deliver a 7-minute lesson introduction with the goal of engaging all students. On the first attempt, the simulation could be set so that students are attentive and compliant, enabling the preservice teacher to fully focus on delivery. In a second session, the simulation can be set so that students are more active and less compliant: A student might question the rationale for the lesson, another might keep looking at their cell phone, and another might express confusion about the presentation. The experience can be made more or less complex based on the learner’s current skills and needs. The types of interpersonal skills to practice will largely depend on what theoretical knowledge learners would benefit from applying to authentic situations.

Researchers have examined the use of this technology to support teaching skills across general education (Dieker et al., 2014), special education (Dieker et al., 2016), supporting English learners (Regalla et al., 2016), and educational leadership (Storey & Cox, 2015). There is also an ever-growing body of literature supporting its use to prepare teachers for classroom management (e.g., Hudson et al., 2019) and to develop skills for supporting students with disabilities including autism spectrum disorder (Vince Garland, Holden, & Garland, 2016).

Research exploring mixed reality use with K-12 students is quite limited, but there is some evidence of its success in teaching behavioral skills to children with autism spectrum disorder (Aresti-Bartolome & Garcia-Zapirain, 2014). Furthermore, in a comprehensive literature review of the use of MRS, augmented reality, and virtual reality in K-12 settings, Melanie Maas and Janette Hughes (2020) found that they have been used to enhance students’ learning and engagement in the sciences and English as a second language; however, they found only three relevant research studies that have been published to date.

We hypothesize that it will prove to be less stressful for students to practice skills by interacting with avatars, before and/or alongside experiences with real people. If they make a mistake or find themselves unsure how to proceed, they can go back and start fresh, again and again, with no harm done to the avatar and no social consequences for the student (Murphy & Cook, 2020).

Using MRS to teach interpersonal skills

To date, most of the research using MRS in elementary and secondary school settings has focused on preparing teacher educators to be more effective (e.g., Dieker et al., 2008), to support students in content instruction (e.g., Lindgren et al., 2016), or to support teacher collaboration skills (e.g, Driver, Zimmer, & Murphy, 2018). No previous studies explored the utility of MRS to support social-emotional skills instruction, but we were encouraged by the findings in teacher education and wondered how this tool would translate with children as part of a SEL intervention (Murphy & Cook, 2020). Our study took place in an after-school program that served children in grades K-2 (before the COVID-19 pandemic). Four participating students (two boys, two girls) received an enriched SEL curriculum titled Storybooks and Social Hooks (SASH) that uses dialogic reading to engage children in shared discussions focused on the development of SEL skills.

Dialogic reading involves readings and conversations in groups or reading dyads. As the teacher, counselor, or parent reads, they ask a series of questions that guide the children in engaging with the story and each other as they share their own experiences and thoughts about the story (Cook et al., 2017). The idea is to encourage children to shift from listening passively to participating actively in discussing and reacting to what is being read.

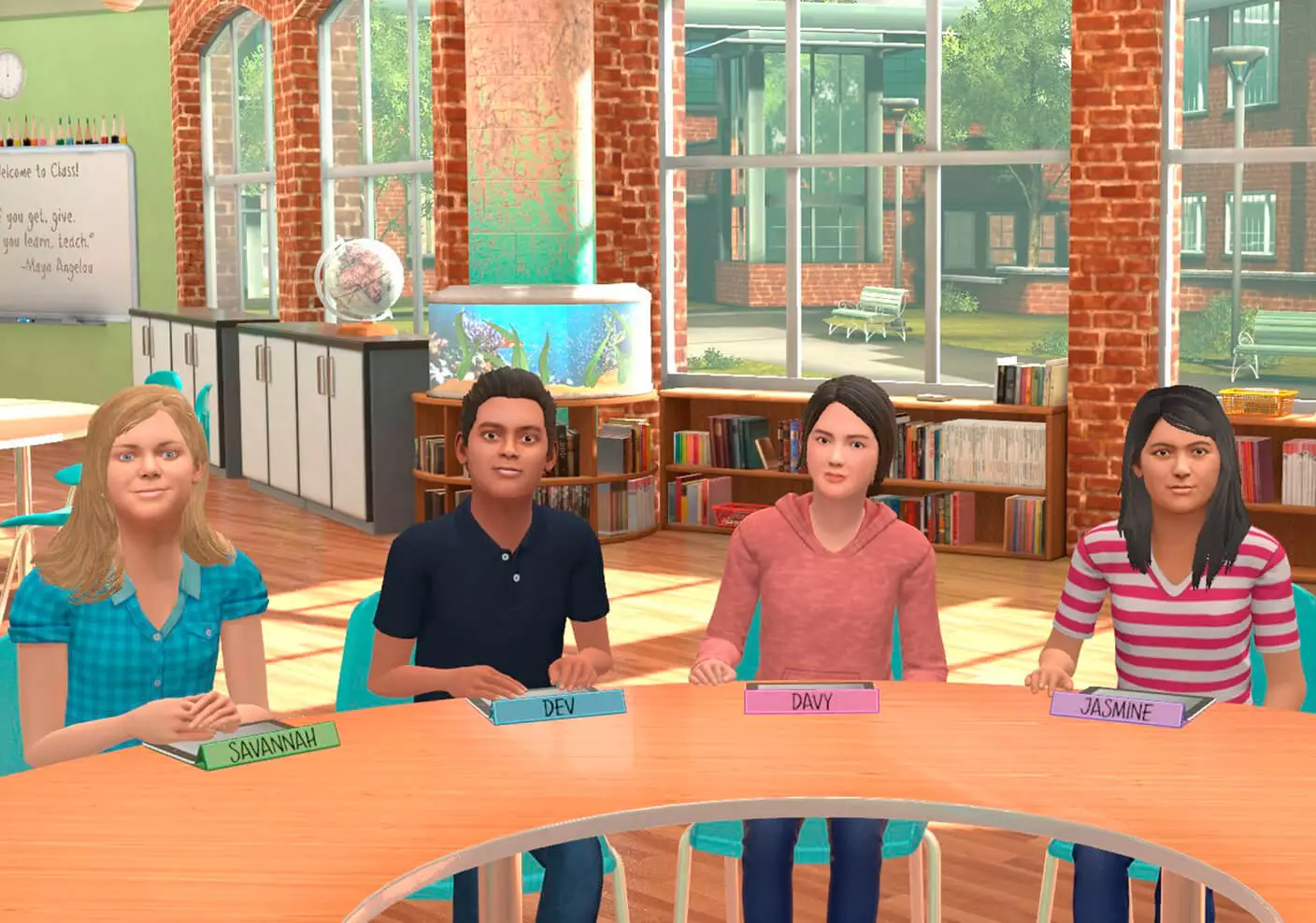

During intervention sessions, the children spent about 15 minutes engaged in dialogic reading of a culturally relevant storybook that depicted characters learning about and engaging in one of three SEL skills (positive communication, positive peer feedback, or problem solving). Then, the children spent about 15 minutes role-playing either with a partner in the group or with MRS avatars on the Mursion platform.

The simulations were designed to be a collaborative group experience in which the avatars represented other children. The children all sat together at a horseshoe table, with the large television monitor at their eye level displaying the racially diverse avatars, also seated in a horseshoe. The children engaged with the avatars first through two meet-and-greet sessions where they were introduced to their “new friends” and got to ask one another questions about hobbies and interests. The students experienced a suspension of disbelief and simply treated the avatars as other students in the group. They were not told how the simulations operated.

During subsequent sessions, the MRS avatars behaved in ways designed to encourage the students to apply the social-emotional skills presented in the book. For example, after reading a book that focused on positive peer feedback, the children and avatars were invited to share artwork they made. During the simulation, the avatars displayed reluctance to share their work, which gave the children an opportunity to provide positive encouragement and compliment their artwork.

Finally, to practice generalizing the skills, the children engaged in about 20 minutes of supervised free play together, while observers looked for displays of the specific skills taught in the social skills lessons.

We rated the children’s skills based on direct observation as well as qualitative data from interviews with the children, parents, and after-school program staff at the end of the curriculum. Our observations revealed statistically significant growth in all three SEL skills taught (i.e., positive communication, positive peer feedback, and problem-solving skills), especially during MRS sessions. The interviews indicated that children developed listening and communication skills and that parents saw increased interest in reading and literacy skills.

Promising aspects of MRS

Based on our experiences implementing MRS with children, in addition to our experiences using this technology in higher education over the past five years, we believe MRS is a promising educational technology-based learning tool for children. However, we also acknowledge that the interest in using MRS, particularly to enhance social-emotional learning may not yet be widely supported. And, as with any new technology, implementation will present challenges.

MRS can offer a safe space for children to practice complex interpersonal skills and receive on-the-spot coaching and feedback before having to use these skills with real classmates who might be affected by the child’s mistakes (Murphy, 2019). If the learner engaging in a simulation is unsure what to do or an adult observer realizes the learner needs intervention, they can pause the simulation. When the simulation is paused, the avatars disappear, and the student can then ask their peers and/or coach for feedback and support before pressing play and returning to the simulation, either by starting over or picking up where they left off (Murphy & Cook, 2020). In this way, engaging in MRS to practice interpersonal skills allows learners to experience less frustration and reduces the fear of making a mistake. For example, in a review of the literature examining the application of various technologies, including MRS, Nuria Aresti-Bartolome and Begonya Garcia-Zapirain (2014) found that children with autism spectrum disorder feel a reduced sense of anxiety when practicing skills in the controlled MRS environment, compared to real social situations.

After 7-10 minutes of MRS, the student engages in a debrief and feedback session with others present where they reflect on what they learned and think about implications for real-life experiences (Murphy, Cash, & Kellinger, 2018). Such opportunities are difficult to create in the real world, where interactions are less predictable.

Also, MRS scenarios can be practiced again and again. After a student has engaged in a specific simulation, received coaching and feedback, and reflected on what they learned, they can practice the same simulation, at the appropriate level of difficulty, until they reach mastery. Such repeated (or distributed) practice of the same content or material in multiple sessions over time is associated with higher levels of knowledge acquisition when compared to highly concentrated practice occurring in one session or over a short time frame (Dunlosky et al., 2013; Logan et al., 2012).

Challenges of implementing MRS

No technology is perfect, and the evidence base related to MRS in K-12 educational settings is only just beginning to emerge. Thus, schools considering the potential use of MRS should be aware of certain key challenges related to its implementation and sustainability. First, MRS requires a highly trained simulation specialist to participate with learners during all simulations. A school can partner directly with Mursion or TeachLivE and schedule sessions with their internal staff of simulation specialists, or a school or school district can pay for their own site license, which would enable them to hire their own staff of simulation specialists. Until technology becomes sophisticated enough to rival the responses of a live human, MRS cannot be an on-demand activity. A school’s ability to implement MRS will depend on the availability of simulation specialists.

A second challenge is that the use of MRS is an ongoing expense. And the cost goes up if schools have specific needs. When subscribing to a platform like Mursion, clients receive access to a library of scenarios. It is possible to design a custom scenario to meet unique needs, but with an additional cost for design and simulation specialist training. Because both research and practice using mixed reality with K-12 students is still very much in its infancy, the library of predeveloped scenarios consists of exercises for adults. There is a need and opportunity for education professionals to develop and pilot scenarios for young learners, but there are costs in time, labor, and money.

Additionally, school staff and students need access to proper equipment and a strong enough internet connection to ensure smooth communication with and viewing of avatars. And, finally, because the benefits of MRS come with repeated practice, implementing it effectively involves ongoing cost and time commitments.

Exploring the possibilities

As researchers and practitioners continue to explore the potential applications of MRS in K-12 settings, we recommend investigating their use across different age groups and content areas, including for SEL and with diverse learners, such as students with disabilities and English learners. It may also be helpful to explore the application of MRS in ways that scaffold student learning across the tiers of current multitiered systems of support (MTSS). Research on MRS implementation situated within an MTSS framework could explore ways to support all students, including those identified as at-risk, while addressing barriers that limit growth and development. There are also questions to be explored associated with what types and doses of learning are most appropriate and feasible for student engagement with this technology.

As we consider the use of mixed reality in K-12 school communities, there are many challenges and questions to consider. However, MRS also has exciting possibilities: We believe that mixed reality holds promise for children to actively practice complex interpersonal skills alongside peers and with the support of adults in both virtual and physical spaces. We encourage our researcher and practitioner colleagues to continue to explore the capabilities of working with avatars. Social-emotional learning is more important than ever, and we must continually reconsider how we are supporting children to thrive and reach their goals in an evolving technological and social landscape. We look forward to witnessing and exploring more applications of MRS and other innovative technology that promote active engagement and collaboration so that even when we are remote, we are most definitely still together.

References

Aresti-Bartolome, N. & Garcia-Zapirain, B. (2014). Technologies as support tools for persons with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. International Research of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11, 7767-7802.

Brownell, M.T., Chard, D., Benedict, A., & Lignugaris, B. (2018). Preparing general and special education preservice teachers for response to intervention: A practice-based approach. In P.G. Pullen & M.J. Kennedy (Eds.), Handbook of response to intervention and multi-tiered systems of support (pp. 137-161). New York, NY: Routledge.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2020a). Social and emotional core competencies. Chicago, IL: Author. www.casel.org/social-and-emotional-learning/core-competencies

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2020b). CASEL cares initiative: connecting the SEL community: Resources. Chicago, IL: Author. www.casel.org/resources-covid

Cook, A.L., Silva, M.R., Hayden, L.A., Brodsky, L., & Codding, R. (2017). Exploring the use of shared reading as a culturally responsive counseling intervention to promote academic and social-emotional development. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 3 (1), 14-29.

Cruickshank, D.R. & Broadbent, F.W. (1970). Simulation in preparing school personnel. Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Teacher Education.

Diana, T.J. (2013). Microteaching revisited: Using technology to enhance the professional development of pre-service teachers. The Clearing House, 86, 150-154.

Dieker, L., Hynes, M., Hughes, C., & Smith, E. (2008). Implications of mixed reality and simulation technologies on special education and teacher preparation. Focus on Exceptional Children, 40 (6), 1-20.

Dieker, L., Lignugaris-Kraft, B., Hynes, M., & Hughes, C. (2016). Mixed-reality environments in teacher education: Development and future applications. In B.L. Ludlow & B.C. Collins (Eds.), Online in real time: Using Web 2.0 for distance education in rural special education (pp. 116-125). Morgantown, WV: American Council on Rural Special Education.

Dieker, L.A., Rodriguez, J.A., Lignugaris-Kraft, B., Hynes, M.C., & Hughes, C.E. (2014). The potential of simulated environments in teacher education: Current and future possibilities. Teacher Education and Special Education, 37 (1), 21-33.

Driver, M., Zimmer, K., & Murphy, K. (2018). Using mixed reality simulations to prepare preservice special educators for collaboration in inclusive settings. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 26 (1), 57-77.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K.A., Marsh, E.J., Nathan, M.J., & Willingham, D.T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14, 4-58.

Grossman, P. (2005). Research on pedagogical approaches in teacher education. In M. Cochran-Smith & K.M. Zeichner (Eds.), Studying teacher education: The report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education (pp. 425-476). Washington, DC: Erlbaum.

Hayes, A.T., Straub, C.L., Dieker, L.A., Hughes, C.E., Hynes, M.C. (2013). Ludic learning: Exploration of TLE TeachLivE and effective teacher training. International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations, 5, 20-33.

Hudson, M.E., Voytecki, K.S., Owens, T.L., & Zhang, G. (2019). Preservice teacher experiences implementing classroom management practices through mixed-reality simulations. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 38 (2), 79-94.

Lave J. & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lindgren, R., Tscholl, M., Wang, S., & Johnson, E. (2016). Enhancing learning and engagement through embodied interaction within a mixed reality simulation. Computers & Education, 95, 174-187.

Logan, J., Castel, A., Haber, S., & Viehman, E. (2012). Metacognition and the spacing effect: The role of repetition, feedback, and instruction on judgments of learning for massed and spaced rehearsal. Metacognition and Learning, 7, 175-195.

Maas, M.J. & Hughes, J. (2020). Virtual, augumented and mixed reality in K-12 education: A review of the literature. Technology, Pedagogy, and Education, 29 (2), 231-249.

Mahoney, J.L., Durlak, J.A., & Weissberg, R.P. (2018). An update on social and emotional learning outcome research. Phi Delta Kappan, 100 (4), 18-23.

Murphy, K.M. (2019). Working with avatars and high schoolers to teach qualitative methods to undergraduates. LEARNing Landscapes, 12 (1), 183-203.

Murphy, K.M., Cash, J., & Kellinger, J.J. (2018). Learning with avatars: Exploring mixed reality simulations for next-generation teaching and learning. In J. Keengwe (Ed.), Handbook of research on pedagogical models for next-generation teaching and learning (pp. 1-20). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Murphy, K.M. & Cook, A.L. (2020). Mixed reality simulations: A next generation digital tool to support social-emotional learning. In M.T. Grassetti & J. Zoino-Jeannetti (Eds.), Next generation digital tools and applications for teaching and learning enhancement (pp. 1-15). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Putnam, R.T. & Borko, H. (2000). What do new views of knowledge and thinking have to say about research on teacher learning? Educational Researcher, 29, 4-15.

Regalla, M., Hutchinson, C., Nutta, J., & Ashtari, N. (2016). Examining the impact of a simulation classroom experience on teacher candidates’ sense of efficacy in communication with English learners. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 24 (3), 5-35.

Singh, S., Roy, M.D., Sinha,K., Parveen, S., Sharma, G., & Joshi, G. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: A narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Research, 293.

Storey, V.J. & Cox, T.D. (2015). Utilizing mixed reality to building educational leadership capacity: The development and application of virtual simulations. Journal of Education and Human Development, 4, 41-49.

Straub, C., Dieker, L., Hynes, M., & Hughes, C. (2015, June). Using virtual rehearsal in TLE TeachLivE™ mixed reality classroom simulator to determine the effects on the performance of science teachers: A follow-up study (Year 2). In Proceedings of 3rd National TLE TeachLivE™ Conference (pp. 49-109).

Vince Garland, K.M., Holden, K., & Garland, D.P. (2016). Individualized clinical coaching in the TLE TeachLivE lab: Enhancing fidelity of implementation of system of least prompts among novice teachers of students with autism. Teacher Education and Special Education, 39 (1), 47-59.

Yadav, A., Bouck, E., Da Fonte, A., & Patton, S. (2009). Instructing special education pre-service teachers through literacy video cases. Teaching Education, 20 (2), 149- 162.

Subscribe for the latest Mursion articles and updates.

By clicking the sign up button above, you consent to allow Mursion to store and process the personal information submitted above to provide you the content requested. View our Terms and Conditions.